One thing we really wanted to do in Japan was visit the Setouchi Triennale in the Seto Inland Sea, in the southern part of Japan. Debbie discovered it in July during her deep research phase—a good thing, since the planning turned out to be epic. Tickets for some of the museums had to be booked months in advance because they sell out early — even back in July we couldn’t reserve a visit to every location that we wanted to see. We also had to make train reservations to Takamatsu, find a place to stay, and make sure it was close to the ferry port—since we would need to be on a ferry early each morning.

Most days we woke up around 6am, just to get in line for the ferry to Naoshima. Even with a “ferry passport” of prepaid fares, we still had to queue to secure a spot. Once on the islands, we got around by walking, taking local buses, or riding the electric bikes that we had luckily reserved months earlier – July!

The event organizers do an incredible job managing the crowds. There’s a Triennale app that provides real-time updates on weather, schedules, and congestion levels for ferries, islands, and museums. We kept getting warning alerts about high crowds, but once we arrived at an island, it rarely felt overly crowded. That is intentional—the festival organizers clearly limit visitor numbers so that everyone can have the best possible art-viewing experience. All tickets are either passes for a particular date, and sometimes for specific timed entry, which also helps.

A Little About the Triennale

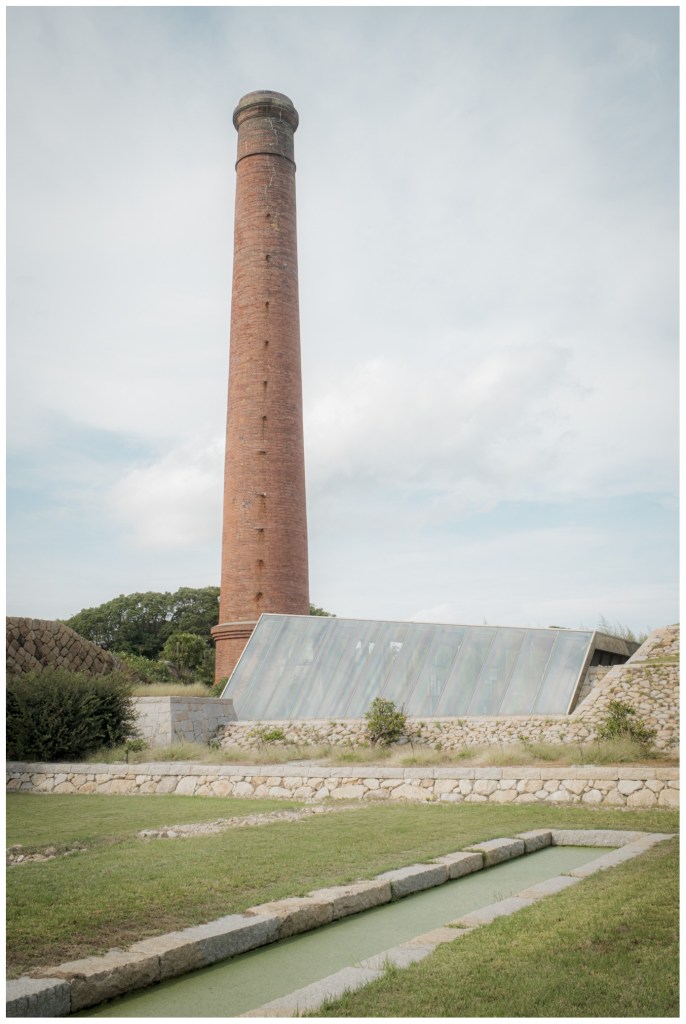

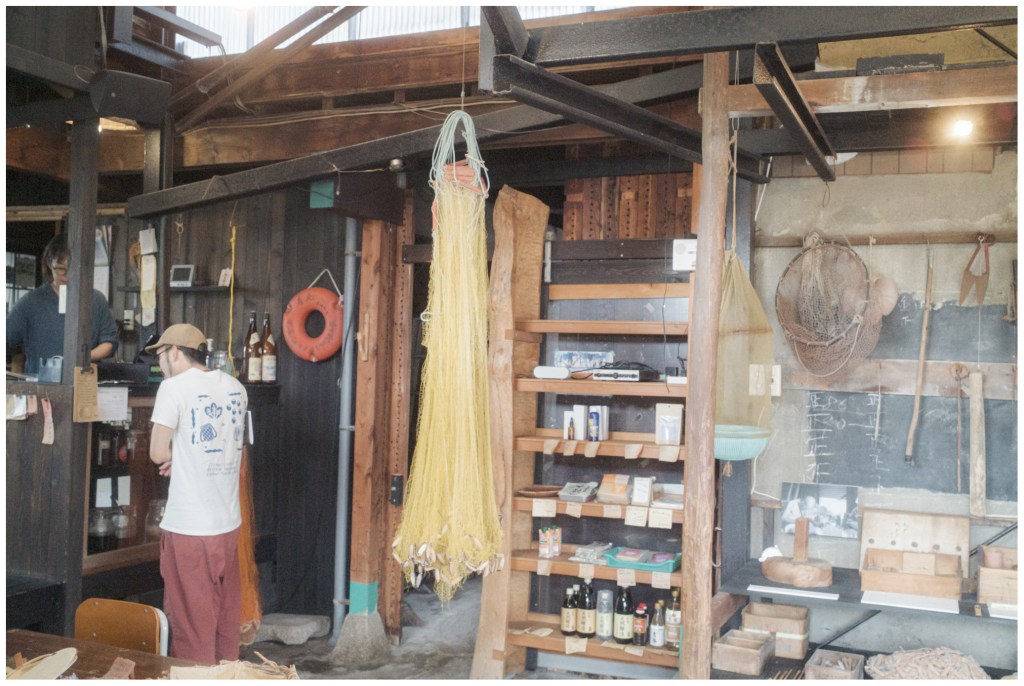

The Setouchi Triennale is a contemporary art festival that takes place every three years across the islands of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea. Rather than gathering visitors into galleries, it turns the islands themselves into living exhibition spaces—old schools, fishing ports, and abandoned homes transformed into installations.

The festival began in 2010 as a way to bring new life to rural island communities facing depopulation and aging, using art as both catalyst and bridge. Each festival spans three seasons—spring, summer, and autumn—encouraging travelers to experience how light, sea, and community shift throughout the year. It’s less about looking at art and more about moving through it.

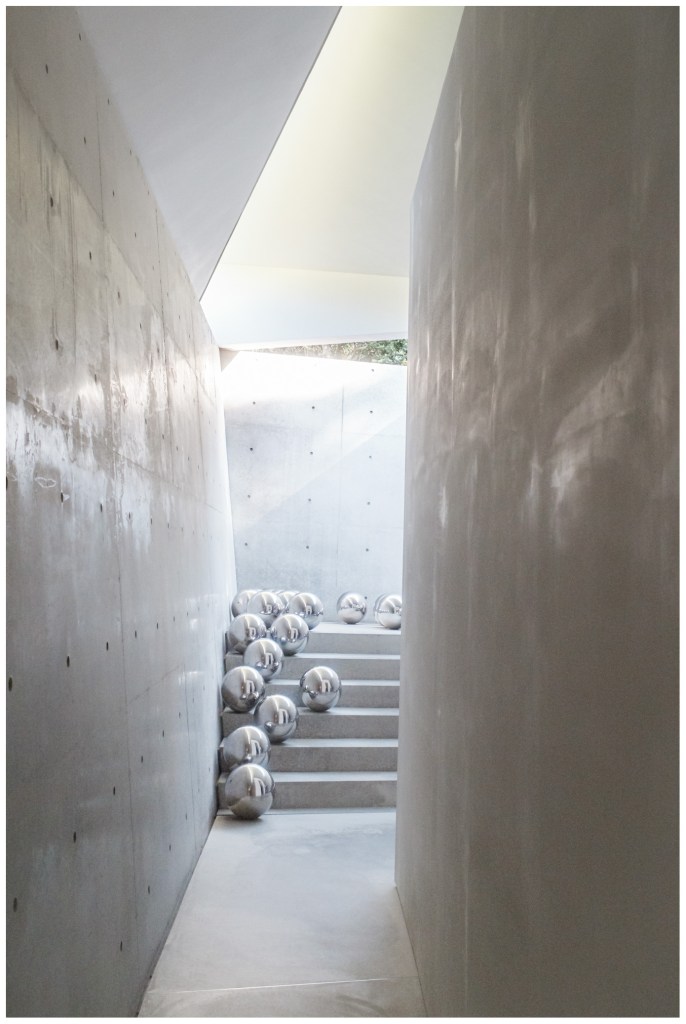

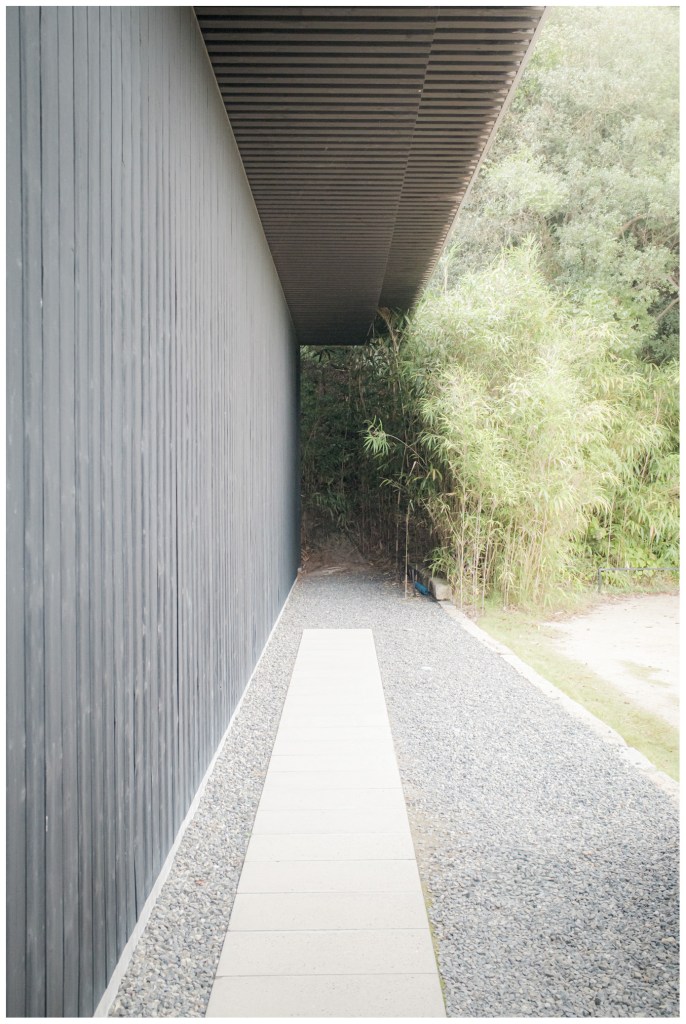

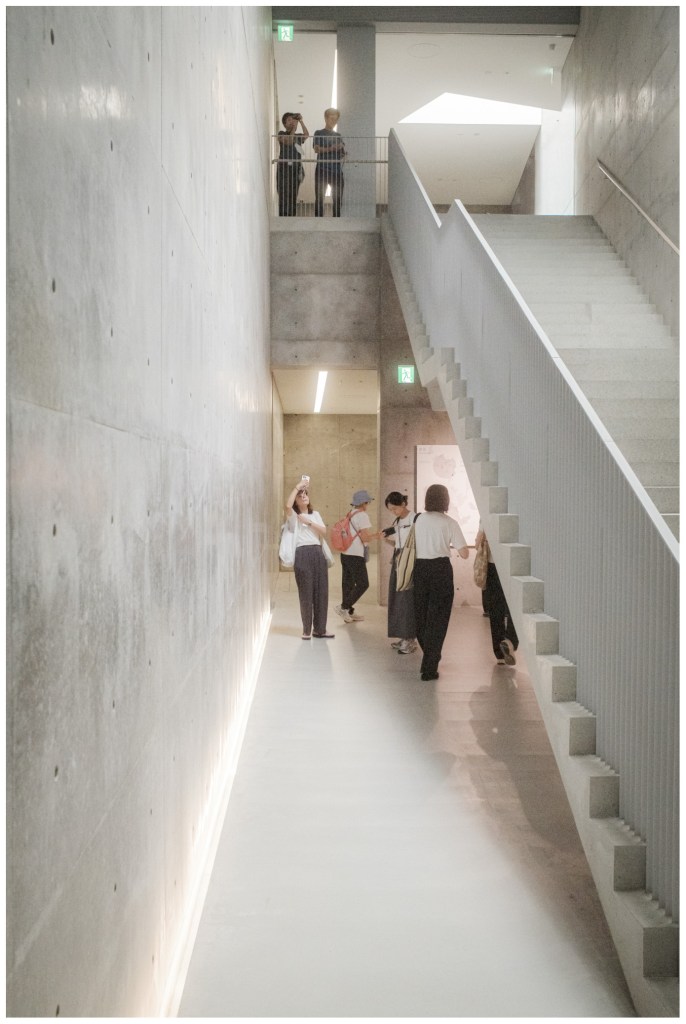

In the larger, permanent museums there’s a close collaboration between architect, artist, and installation. Many of the museums were created through the vision and funding of the Benesse organization, which continues to serve as the Triennale’s philosophical anchor. The Naoshima musuems were developed in partnership with architect Tadao Ando, who created spaces that blur the boundaries between architecture, art, and nature—embodying the festival’s larger mission to revitalize island life through creativity.

You can read more about it here in a recent New York Times article:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/31/arts/design/japan-island-naoshima-art-museum-tadao-ando.html

In most of the museums we weren’t allowed to take pictures, but I did manage to capture a few where I could that I hope reflect the feeling of the islands—the architecture, the landscape, and the people. The larger museums also sell beautiful books documenting the installations.

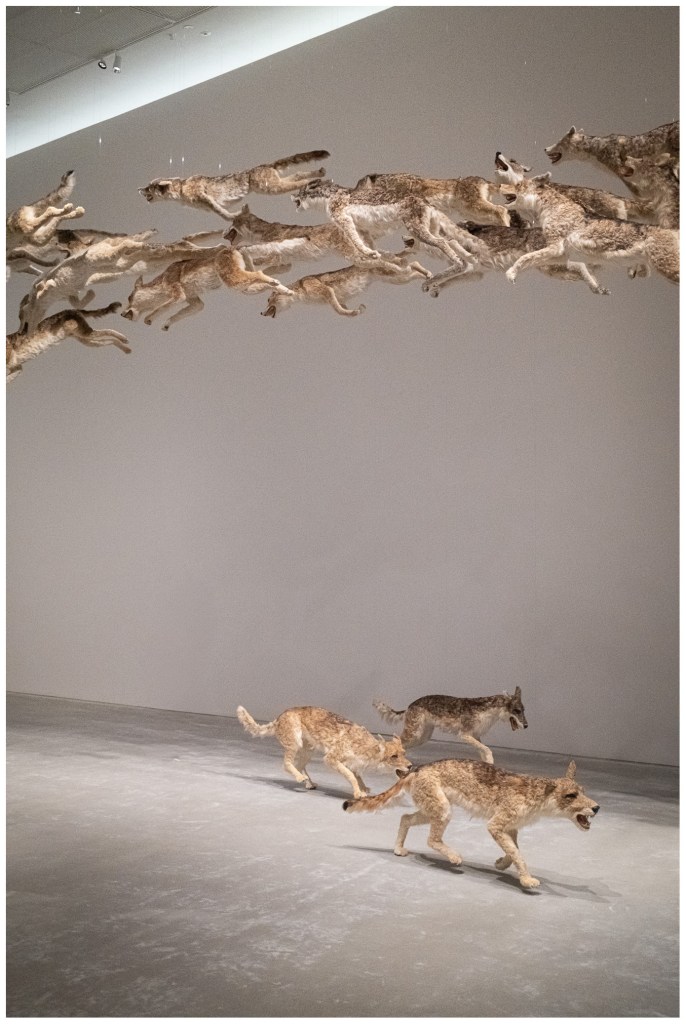

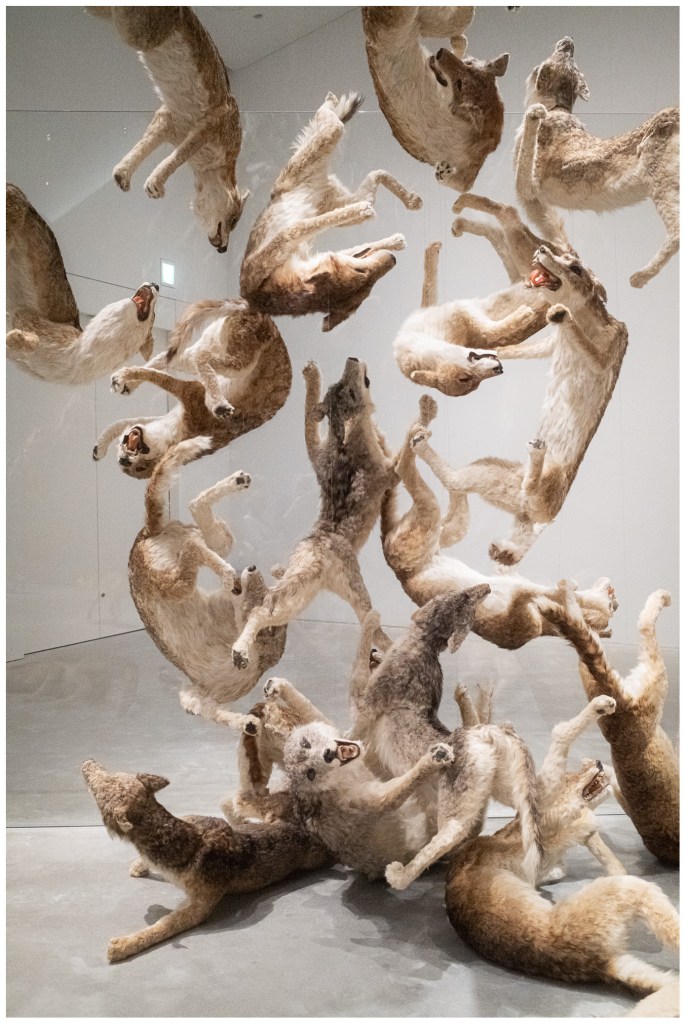

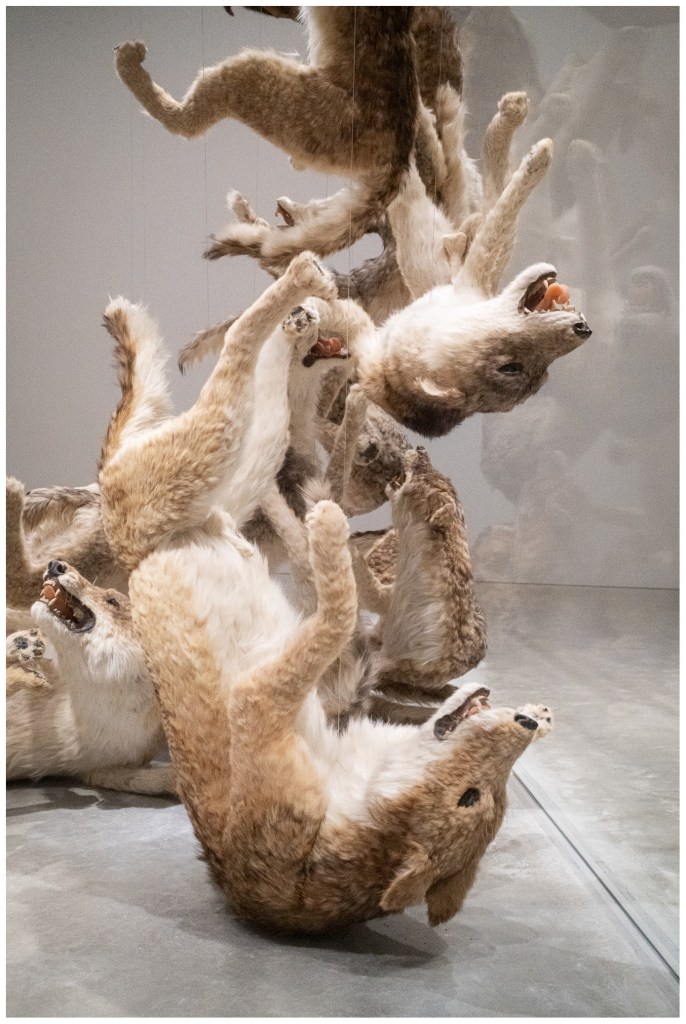

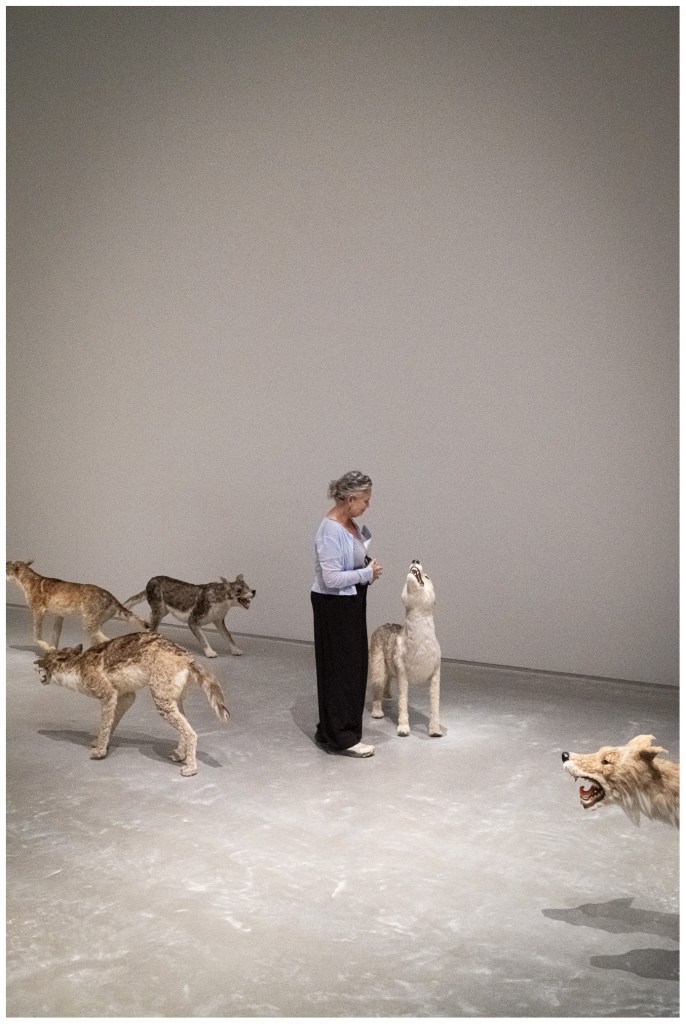

Within the Naoshima New Museum of Art there is one piece that stopped us both in awe (and deserves it’s own gallery section below). The Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang‘s 2006 piece “Head On.” I had read about it some time ago and was surprised when I rounded the corner from one gallery to the next, and was suddenly inside this huge installation. Here, realistically-rendered packs of wolves seem to race in a circle from the ground, to flying through the air, to crashing into a glass panel in a violent pile. It is intended to represent a cycle of anger, ambition, and group-think. We spent a lot of time there. Viewing it from different angles and watching other people’s reactions as they entered the space. The images in no way can do justice to the work’s in-person impact.